The question of the day is: will the nation’s largest nuclear power utility, Exelon, survive? That’s a question that wouldn’t even have been asked a few years ago; Exelon was riding high. But with its stock price down 60% since July 2008, with 55% of its electricity coming from aging and increasingly uncompetitive nuclear reactors, it’s now a valid question, one that Crain’s Chicago Business has been doing an excellent job in covering, especially over the past week.

It’s an important question: Exelon’s future will be, perhaps, the future of nuclear power in the U.S. At the least, its fate certainly will have a magnified impact on that future, and on the ability of other heavily nuclear utilities to navigate the new utility era they suddenly find themselves in. But to make a real attempt to answer the question requires a little more background and perspective.

Background

“The more things change, the more they stay the same.” That’s a truism, a way of attempting to make sense of changing circumstances. It has been perhaps sometimes an accurate assessment of change: on a macro level it’s hard to deny that in some ways things haven’t changed that much in the past 50 years. After all, despite moon landings, acid, the internet, smartphones, hybrid cars, the ends of wars and the beginnings of other wars, the various liberation and other movements, and all the other advances, technological and otherwise, that make the U.S. in 2014 a very different country than it was in 1964, the 1% are still on top; indeed, even more so than at any time since the robber baron era. It’s probably fair to ask: what really has changed?

Of course, a lot has changed. And, as the pace of change accelerates, as technology achieves advances not even imaginable a few years ago much less decades ago, as demographics–especially in the U.S.–hurdle us toward a majority minority society, that truism becomes less and less accurate. Even that 1% has changed over the past 50 years; consider this New York Magazine comparison of the 10 largest U.S. companies in 1964 versus 2011 (close enough….). Only two companies, GE and IBM, appear on both lists.

50 years ago, the electric utility industry was the exemplar of that truism. Nothing much actually ever changed for it. Utilities built power plants, went to regulators to ask for rate increases to cover the costs of those new power plants, and earned a tidy rate of return on their investment. It wasn’t an exciting industry and it certainly didn’t attract the best and brightest from the nation’s business schools.

I remember–it was 1964–a stockbroker friend of my dad’s was trying to teach me about Wall Street and the market. He suggested that a great, very safe investment would be bonds in the Washington Public Power Supply System (WPPSS) a quiet public utility in the northwest. I wasn’t even 12 at the time, so had no money to invest of course. But I remembered that recommendation in the early 1980s when WPPSS–or WHOOPS as it was known by then–was the subject of the largest bond default in history. The utility had become way overextended trying to build five new nuclear reactors at the same time–none of which were really needed. Only the controversial Columbia reactor was completed. Hundreds of thousands of people holding on to that “safe” investment lost their money, their retirements, in some cases probably more.

By then, utilities had at least become more interesting than they had been in the past. WPPSS wasn’t the only one that experienced trouble. Public Service of New Hampshire went bankrupt trying to build two reactors at Seabrook, New Hampshire. Others ate billions of dollars in cost overruns. The Zimmer reactor in Ohio, said to be more than 97% complete, was turned into a coal plant because it was going to cost more to finish that last 3% because of construction deficiencies than it was to convert it. It was, to say the least, not exactly a golden era for electric utilities, especially those that had invested heavily in nuclear power.

The advent of deregulation saved the nuclear industry. The faulty implementation of deregulation forced ratepayers to foot the bill for tens of billions–perhaps even hundreds of billions (some $25 billion in California alone) in “stranded costs.” Those were the costs accrued by utilities that built the first generation of nuclear reactors that might never otherwise have been recovered by the utilities. Ratepayers took care of it all, from the enormous cost overruns–800% in the case of Georgia’s first two Vogtle reactors–to the smaller but still stratospheric overruns at every other reactor ever built. Indeed, the average cost overrun for the first generation of reactors was over 300%.

The New Era

But now we’re in a new era. Those old reactors are mostly paid for, yet increasingly they are still not competitive with alternatives, especially gas, wind and solar. The latter two are the growing technologies, and the technologies that are transcendentally different from the utility models of the past. The model of building a power plant and sitting back collecting a fine rate of return until the next power plant is needed is long gone. There is no longer assurance for utilities that a power plant, especially an expensive nuclear reactor, will operate through its planned lifetime. If it can’t compete with alternatives and the fast-changing nature of the electricity generation and distribution system, it may well close, as we’ve seen over the past 18 months and are likely to see again soon.

Increasingly, consumers will drive the utility business, rather than the other way around. When consumers can build their own power plants on their rooftops, at a price competitive with the price for power the utility can sell them, consumers gain the upper hand. The same is true when consumers can band together–even if they don’t have a rooftop–and invest in a power plant for their neighborhood, or interest group, or just as a group of friends. That is what is beginning to happen in the U.S., and throughout the world.

Companies that can envision the future–like IBM could back in 1964 when the idea of a personal computer was science fiction–they’re the ones that survive long-term. Companies that insist on doing things the old way; they’re the ones who litter history’s dustbins.

Whither Exelon?

Thus, it must be absolutely terrifying for Exelon to learn that Crain’s Chicago Business feels compelled to compare the utility–one of the Chicago area’s largest employers–to Kodak and Motorola, two companies that failed to make a needed transition.

Writes Joe Cahill of Crain’s,

“Adaptability isn’t a hallmark of big utilities, which haven’t changed much over the past 100 years. Top companies like Chicago-based Exelon are structured for the existing order, not a murky new landscape. Focused on maximizing current profits, they’d rather pump cash into executive bonuses and share buybacks than invest it in unproven technologies that could wind up cannibalizing their existing business. So they pooh-pooh innovations and tell themselves nothing important will change.

“Exelon CEO Christopher Crane seems to have a particularly strong case of status quo bias. Consider his recent comments on the implications of new technologies: ‘The demise of central station power and the wires and distribution system is grossly overstated at this point,’ Mr. Crane told a gathering hosted by an environmental think tank last month.

“Mr. Crane was referring to ‘distributed generation’ technologies that could dramatically reduce customers’ reliance on utilities for their power. Solar panels, together with high-capacity storage batteries already are enabling consumers and businesses to produce their own electricity. In a role reversal, some customers are selling electricity to utilities.”

Cahill adds,

Dominant companies often fail to anticipate technological advances that upend their industries and destroy their franchises.

It happened to Eastman Kodak Co., which dismissed digital photography, and to Motorola Inc., which lost its lead in cell phones to innovative new rivals. Examples go on and on, from retailing through media and even insurance.

Time and again, complacency, lack of foresight and resistance to change have made corporate giants vulnerable to newcomers wielding new technologies.

Utilities are next up on the Darwinian hit parade. Technologies with the potential to transform the industry are emerging. These innovations enable customers to control their power use, generate their own electricity, and perhaps even leave the traditional electric grid altogether someday. This raises questions about the long-term viability of traditional industry business models and financial structures.

As my colleague Steve Daniels wrote over the weekend in his fine analysis of Exelon Corp., these developments have profound implications for the Chicago-based company and all big utilities. If they can’t adapt to technological change, they risk obsolescence.

“‘We’re way past the point where we’re waiting for breakthroughs in the lab,’ says utility consultant Bob Zabors, CEO of Enovation Partners LLC in Des Plaines. ‘These technologies are all here today.’

“At a minimum, these technologies portend significant changes in traditional industry relationships in which utilities generate and transmit all the power for large geographic markets, while customers flip switches and pay electric bills. Over time, as distributed generation gear becomes more affordable and efficient, it’s conceivable — but by no means certain — that large numbers of customers would abandon the grid, or rely on it only for back-up power.

“‘At that point, the electric utility becomes superfluous,’ NRG Energy Inc. CEO David Crane (no relation to Exelon’s Mr. Crane), told a Chicago audience recently. Expecting the current electric grid to become obsolete in 20 or 30 years, Mr. Crane is positioning NRG for a dramatically different future. Among other things, NRG is acquiring companies that install solar systems.

Exelon’s CEO, meanwhile, is doubling down on traditional utility assets. He recently agreed to pay $6.8 billion for Pepco Holdings Inc., the utility serving metro Washington. That’s a big bet against structural change.”

Indeed, the Pepco deal is now critical to Exelon’s future. Writes Steve Daniels of Crain’s, “Still, Mr. [Christopher] Crane told analysts recently that acquiring Pepco will enable Exelon to finance its dividend entirely with earnings from regulated businesses—no small benefit. Investor memories remain fresh of the 41 percent dividend cut Exelon felt compelled to make last year as revenue and earnings were dropping.”

In other words, Exelon wants to take the money it earns from customers in the Washington DC area to make up for its losses elsewhere.

But what if the Exelon/Pepco merger doesn’t get approved? It needs approval from several entities, not the least of which are the Washington DC Public Service Commission and the Maryland Public Service Commission. Both have a history of rejecting such mergers, especially with companies too involved with nuclear power.

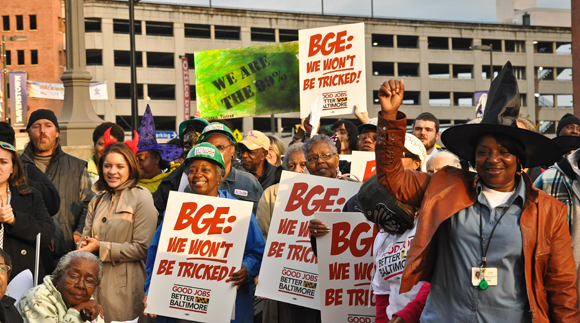

In the 1990s, Baltimore Gas & Electric wanted to merge with Pepco. But concerned in part about BG&E’s nuclear exposure (Pepco has no nuclear power, at the time BG&E operated two units at Calvert Cliffs, Maryland) and other factors, the Washington DC PSC rejected the deal.

Later on, Florida Power & Light tried to merge with BG&E. But Maryland regulators didn’t see any benefit to Maryland ratepayers in that deal, and rejected it as well.

BG&E eventually became part of Constellation Energy, which actually was taken over by Exelon in 2012, with approval of the PSC. But by then, Constellation was a shell of its former self–it had very nearly gone bankrupt in 2007 and had to be bailed out by Warren Buffett. One officially unstated but key part of the Exelon takeover: a promise from then-CEO John Rowe that Exelon wouldn’t try to resume construction of Constellation’s ill-fated Calvert Cliffs-3 reactor, which that company already had given up on.

Approval of the Pepco/Exelon merger would mean that the vast majority of Marylanders–in both the Washington and Baltimore metro areas, would get their electricity from a single company based in Chicago, and one which already has stated it wants to take the money from that area and use it to cover their existing losses elsewhere to keep up its dividend to shareholders. Where’s the benefit in that for Maryland? The Maryland PSC will be looking at this deal very skeptically.

And if the Washington DC PSC was concerned about BG&E’s limited nuclear assets, how is it going to feel about the idea of submitting Washington ratepayers to the exposure of the most nuclear company in the nation? Radioactive waste disposal costs, decommissioning costs, uncompetitive and aging reactors, possible accident costs? These are all foreign issues for Washington–and may not be exactly where the DC PSC wants to go, especially, again, with a company headquarters hundreds of miles away instead of a few blocks down the street.

Moreover, Pepco, while also a fairly traditional utility, at least is developing some stake in the new utility model. For example, the city of Washington is aggressively touting solar power now. Pepco is currently using a grant from the federal Department of Energy to learn how to better integrate distributed solar power into its grid. Exelon, on the other hand, while paying lip service to renewables, has been waging an active campaign against them–because they’re providing power cheaper than Exelon’s reactors can.

Which way will the DC PSC want to go?

There are other states and federal agencies that will have to weigh in as well. If the merger doesn’t go through–and denial by only one jurisdiction can end it entirely–where does that leave Exelon?

It leaves it with the nation’s largest fleet of nuclear reactors and power that it can’t sell on the open market. It leaves it with an old business model that is becoming increasingly and speedily obsolete. There has been talk about Exelon trying to spin off its nuclear facilities into a separate entity–but who would want that albatross?

As former Exelon CEO John Rowe told Crain’s in an e-mail, “In hindsight, I should have sold a piece of our nuclear when times were good and taken more risk on (transmission and distribution) assets, but I did not. It would not have been an easy thing to do anyway.”

It would be an even harder thing to do now.

All of this is what is behind Exelon’s current desperation and its creation of the front group Nuclear Matters–an effort to try to save its aging reactors regardless of the cost (and dangers) to ratepayers and its full-scale lobbying campaigns now going on in Illinois and elsewhere. Says Crain’s, “Likewise, Mr. Crane and the company are lobbying federal regulators and Illinois lawmakers on policy changes that would boost the bottom line of Exelon’s ailing nuclear fleet, especially its six plants in Illinois, where competition from wind farms has rendered three plants on Exelon’s westernmost flank money-losers, according to the company. A controversial state legislative effort to save the facilities is expected next year.”

Exelon successfully lobbied the Obama Administration and EPA to include some help for those reactors in its proposed carbon reduction rules. Clean energy advocates, including NIRS, are trying to get those subsidies out of the final version (for example, here). And, it’s possible that will be too little, too late for Exelon anyway.

Exelon has now started lobbying its friends to give it a hand. This week, Nuclear Matters unveiled a new page on its website (which is run not by Exelon or a private organization, but by the Sloan PR firm) listing corporate supporters of Exelon’s effort, including nuclear utilities like Next Era Energy, Ameren, Pacific Gas & Electric, Omaha Public Power District, Dominion, Energy Northwest, and more.

Our guess is that these companies are not contributing financially to Exelon’s campaign, but that’s only a guess. Activists may want to contact their state regulators to ensure the money you pay your utilities for your electric bills is not money being spent on Exelon’s schemes.

It may not be the case that as Exelon goes, so goes the entire nuclear industry. On the other hand, when a company this large, this dependent on nuclear power, gets as desperate as Exelon is now, as on-the-brink as Exelon increasingly appears to be, that can’t be good news for the nuclear industry. But it can be–with a push from all of us–good news for everyone else.

Michael Mariotte

June 27, 2014

Permalink: https://www.nirs.org/2014/06/27/will-exelon-survive/

You can now support GreenWorld with your tax-deductible contribution on our new donation page here. We gratefully appreciate every donation of any size–your support is what makes our work possible.

Comments are welcome on all GreenWorld posts! Say your piece above. Start a discussion. Don’t be shy; this blog is for you.

If you like GreenWorld, you can help us reach more people. Just use the icons below to “like” our posts and to share them on the various social networking sites you use. And if you don’t like GreenWorld, please let us know that too. Send an e-mail with your comments/complaints/compliments to nirs@nirs.org. Thank you!

Note: If you’d like to receive GreenWorld via e-mail daily, send your name and e-mail address to nirs@nirs.org and we’ll send you an invitation. Note that the invitation will come from a GreenWorld@wordpress.com address and not a nirs.org address, so watch for it.

nice piece!

-Ken

Date: Fri, 27 Jun 2014 20:19:00 +0000 To: kbossong@hotmail.com

Really EXCITING!!!, GREAT article Mr. Mariotte. It means SOOOOO much that you are so knowledgeable and can transfer that in such an easy to understand style. THANK YOU!!!

Apropos the nuke industry’s moves, the NYT had a full page ad promoting the nuclear industry on page A19, 6/18/14. Slogan: “New York’s nuclear energy plants empower us.”

Claims: “Safe, reliable, clean baseload nuclear power energizes New York.” Plus more.

They’re doing that–and spending that kind of money–because they’re afraid New York State and grassroots groups will succeed in shutting down Indian Point. Fitzpatrick in upstate New York is also in trouble.

I hope the grassroots outfits succeed. Has VT Yankee been shut down yet or are they still waffling around?

It’s always been set to close before the end of this year. That hasn’t changed.