If how much is written about a topic is an indication of how important or perhaps timely the topic is, then the issues of distributed generation, the changing nature of how Americans will obtain their electricity, and the effects of both on electric utilities, are of both extreme importance and timeliness. We have been reporting on these issues almost daily, citing articles and adding to the conversation, but today the plethora of articles, opinions, predictions and information–and good ones at that–is almost overwhelming.

That major changes are coming should be obvious to anyone without blinders on–or perhaps anyone who hasn’t overinvested in nuclear power and fossil fuels. The only questions now are how fast those changes will be implemented and how extensive they’ll be.

If you haven’t been following the issue, here’s the brief (and simplified) synopsis: Distributed generation–for the most part small-scale rooftop solar (from your local Wal-Mart to your own house) and wind farms, coupled with increased availability and affordability of electricity storage (primarily batteries) coupled with increased energy efficiency in both buildings and appliances and smart electric grids are completely changing the nature of the electric utility business.

In the 20th century, that business model–designed to bring reliable and relatively affordable (if not often safe or clean) electricity to the entire nation–achieved its goals. Utilities built large “baseload” power plants, typically fossil fuel or nuclear powered plants that run 24/7, and an accompanying transmission grid to take the power from those plants to cities and towns all across the country. Regulators ensured they earned a profit on every step of that process. And the nation was indeed electrified.

But as we entered the 21st century, that business model began to fall apart. Most states chose to deregulate their electric utilities, and separated the jobs of power production from electricity transmission. Instead of regulators setting rates and ensuring profits, utilities began to be forced to compete with each other to sell electricity at the lowest rates to consumers. Inefficient and overly costly power plants began to close–a process that accelerated in 2013 with the unexpected shutdown announcements of five nuclear reactors. More shutdowns–in many cases aided by anti-nuclear campaigns–are likely this year and next. And dozens of dirty coal plants have closed in the past few years as well.

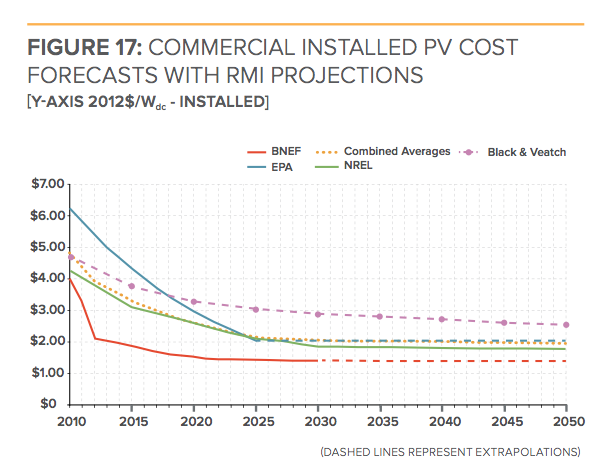

Meanwhile, technological advances, especially the plummeting costs of small-scale solar power and the advent of leasing arrangements which mean that consumers–both businesses and homeowners–can get solar installed on their rooftops without the high upfront costs, have made it possible for millions to produce their own electric power and sometimes even more than they need, which policies called net metering allow for them to sell back to the grid at market, and sometimes above-market prices.

As energy efficiency programs have begun to work, the average household and business is using less electricity than they used to. It now looks like peak electricity use in the U.S. was reached in 2007, and even with population growth we may never again reach that peak.

Wind power costs also have fallen over the years, and in many parts of the country are cheaper than their older competition: nuclear and fossil fuel plants. Smart grids, which are still in their infancy, make it possible for grid operators to more efficiently move between the intermittent power sources like wind and solar farms as their power is produced and wanes, providing more reliable access to renewable energy.

That’s where we are now. Where we’re going, sometimes called Utility 2.0, is what’s really exciting. The “internet of things,” where our devices, soon to include our entire homes and places of work, are connected to the internet, are enabling the smart grid to become really smart–to provide power to where it’s actually needed when it’s actually needed (and not at other times) from where it’s being produced (and in a somewhat similar fashion to the local food movement, that will more often than not be locally).

Electricity storage means that those big baseload plants will become obsolete. At the household level, who needs them when your rooftop solar panels provide all your electricity when the sun is up, and when it’s down you just shift to the batteries that have stored the excess power. Solar power 24/7. On the macro level (after all, most big city downtowns don’t have enough rooftop space to power themselves), larger batteries and other types of storage now in the early stages of commercialization mean that the power from wind, offshore and onshore, and large solar plants such as those sprouting up in California and Nevada (and even New York City’s Fishkills landfill), will also become 24/7. Add in some geothermal power where available, even more increased energy efficiency, the ability for cars to not only run on electricity but to generate electricity, and other technological advances on the horizon, and that old utility model has bitten the dust.

As we noted here on Wednesday, February 26, Rocky Mountain Institute has just released a report on when it will be cost-effective for the average household to just completely leave the grid if it wants–it’s sooner than you think. But whether we will end up with millions of micro-grids or will keep some form of regional grids as we have now is one issue for discussion; the reality staring all in the face is that we won’t have the kind of electric system we have now, and that’s coming sooner than most people think as well.

Traditional utilities are fighting this, of course, the same way all obsolete industries fight to remain relevant until they no longer are. And the nuclear power industry is fighting this too–that’s behind what for it is the absolute necessity of rigging the power markets to favor nuclear power over cheaper (and cleaner) energy sources. Without a rigged market, it can’t survive even in the current reality, much less the one on the way. Clean energy advocates should be actively championing and working towards the future–because it is the pathway to a nuclear-free carbon-free energy system.

Everything that has been said here has been documented in the past two months of GreenWorld, thus I haven’t put up links to each sentence–although I could have. Just scroll through the last two months, as I did yesterday sitting in a hospital room after a minor procedure, and you’ll see that. Even I was amazed at how this has been documented here.

But here are a few more posts I found just this morning that provide some new context and perspective:

Said Rive: Storage is a game-changing product. Those in the game don’t want to change the game. Utilities are trying to delay the game from changing.

Musk added that Tesla is working to create stationary battery packs that will last long, be safe and compact enough for houses. In other words, Musk’s vision is not just for Tesla to eventually become one of the world’s major auto manufacturers, it’s larger that that: it’s to bring Tesla into every household.

Musk also endorsed a carbon tax: The right move is a broad carbon tax. Our taxes for gas are very low compared to the EU. We should tax the things that are bad over the things that are good. Like we tax cigarettes and alcohol more than bread. It seems like common sense. It’s time for us to get serious on a carbon tax on a national basis. It’s economics 101. It’s so obviously the right move, but politicians are afraid of it.

Stephen Lacey is one of the better-informed writers on energy issues. He too sees solar power coupled with battery storage as an existential threat to utilities and in this article explains more about that, while also explaining in greater detail the Rocky Mountain Institute report mentioned above.

Stephen Lacey is one of the better-informed writers on energy issues. He too sees solar power coupled with battery storage as an existential threat to utilities and in this article explains more about that, while also explaining in greater detail the Rocky Mountain Institute report mentioned above.

John Farrell at the Institute for Local Self Reliance is another who has been writing extensively on these issues. In this article, he asks: Is utility 2.0 a forecast or a post-mortem? And he concludes that for many utilities, it’s the latter–it may already be too late for them to jump on board–although some commenters disagree. Snippet:

Look at Georgia Power. They’re struggling to complete new reactors at their Vogtle nuclear power plant, and costs are rising despite over $8 billion in federal loan guarantees. But thanks to a coalition of environmentalists and the Georgia Tea Party, the state’s public utilities commission has required the utility to invest in distributed solar power. The utility will get 525 MW of new clean power generation, years before either new reactor will generate a single kilowatt-hour. And by 2017, the earliest the reactors could come online, it will cost less for Georgia Power customers to get solar energy from their own rooftop than to buy it from the utility.

Finally, David Crane, CEO of NRG Energy, which owns 53,000 MW of power plants, most of it fossil fuels, but also some nuclear and some renewables, has been outspoken on the need for utilities to adapt to the new model. In this article, he says it is “shockingly stupid…to build a 21st-century electric system based on 120 million wooden poles….” Crane has famously said he believes the new system will take about as long as it has taken smartphones to supplant landlines (though obviously that remains a work-in-progress), and that rooftop solar is the future. Here he even admits that NRG’s own power plants could become a liability for the company in the not-so-distant future. Crane is no anti-nuclear advocate, in fact he remains a supporter of nuclear power, but adds that there is no support in either the political arena nor private sector for traditional reactors or small modular reactors. The article goes on: Beyond nuclear, Crane said that the public’s perception of renewable energy technologies is vastly more positive than it was even a few years ago. “Green doesn’t mean a compromise of capability and price,” he said, adding that consumer products like Tesla S are “kicking ass.”

Michael Mariotte

Comments are welcome! Say your piece above. Start a discussion. Don’t be shy; this blog is for you.

If you like GreenWorld, you can help us reach more people. Just use the icons below to “like” our posts and to share them on the various social networking sites you use. And if you don’t like GreenWorld, please let us know that too. Send an e-mail with your comments/complaints/compliments to nirs@nirs.org. Thank you!

Note: If you’d like to receive GreenWorld via e-mail daily, send your name and e-mail address to nirs@nirs.org and we’ll send you an invitation. Note that the invitation will come from a GreenWorld@wordpress.com address and not a nirs.org address, so watch for it.

0 responses to “Why we’re writing so much about the changing nature of the electricity business–everybody else is. Oh, and because it’s important.”