A generation or so ago, New England was one of the most nuclear-dependent regions in the nation. If one defines New England as including New York, then that relatively small corner of the U.S. map was home to 15 commercial nuclear reactors 25 years ago–only the state of Illinois had a more concentrated nuclear presence; regionally, no other area is even close to that concentration on a square-mile basis.

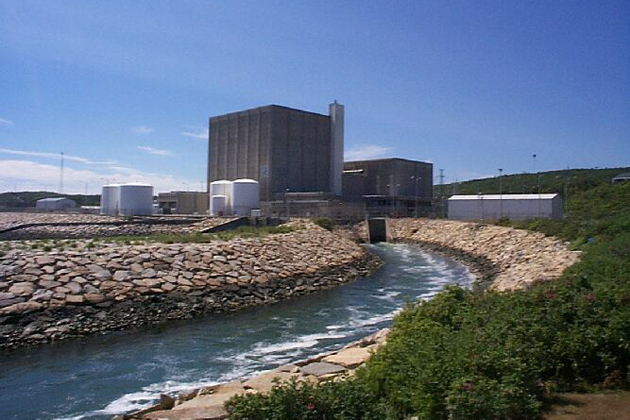

Today, New England is leading the nation away from nuclear power, and toward the energy efficient, renewables-powered system of the 21st century. Today’s news from Entergy that it will close its Pilgrim reactor by mid-2019–and probably a whole lot sooner–is just the latest manifestation of that process, and it’s a process that is accelerating.

It is probably not a coincidence that for the past 25 years, New England has been home to the most active and aggressive anti-nuclear movement in the U.S. When people band together, work together, and stick to it: good things happen.

The shutdowns started with Yankee Rowe in 1992, which wanted to become the first reactor in the U.S. to receive a 20-year license extension and instead closed for good when Citizens Awareness Network proved it was too unsafe to operate. Then came Millstone-1, followed by Connecticut Yankee and Maine Yankee in 1996. Last year, it was Vermont Yankee that ended operations.

It is true, on one hand, that the poor economics of nuclear power have come home to roost particularly hard in New England, and that at the root of every shutdown in the region has been the reactors’ inability to compete in the marketplace. But it is just as true that those economics exist elsewhere in the country–just check Illinois, for example–and the shutdowns have been much slower elsewhere. The citizens’ actions have made a real difference–and the lesson is they can elsewhere too.

In Pilgrim’s case, Entergy admits it is losing $10-40 million (and think the higher figure) per year just trying to run that obsolete Fukushima-clone reactor. And actually trying to bring Pilgrim up to basic NRC safety standards, which it does not meet–the NRC has rated Pilgrim and two other Entergy reactors in Arkansas as the worst in the nation–would cost many millions more. So for Entergy, the decision was easy: cut its losses now, and avoid spending money to make the safety improvements.

Cutting its losses now is why Pilgrim is not likely to actually operate until mid-2019, as its shutdown announcement indicated. That date is when Entergy has promised the New England grid that it would provide power from Pilgrim. But doing so would cost Entergy a lot of money; if the company can get out of those commitments, it will be happy to do so. And it’s highly likely other capacity can be brought in, probably by mid-2017, to take Pilgrim’s place.

Explained Julien Dumoulin-Smith, a UBS analyst: “We see the Pilgrim plant retirement as a positive in so far as the company is closing” it, adding: “We suspect the company could well opt to retire the plant early (May, 2017), even if [it ends up] paying a premium to secure additional capacity.”

Dumolin-Smith added, “we expect [Entergy] to announce a comparable decision around its Fitzpatrick unit in coming weeks.”

And indeed, Entergy’s Fitzpatrick reactor in upstate New York is in a similar money-losing situation as Pilgrim. Entergy says it will make a decision on Fitzpatrick’s future by the end of the month. From a financial perspective, there is only one alternative for Entergy: close Fitzpatrick as soon as possible. But, unlike Pilgrim, which seemed to have no supportive constituency at all, upstate New York is heavily Republican and its regional politicians want to save the reactor whatever the cost to ratepayers. So they are making a last-ditch effort to try to find some way (read: subsidies) to keep the reactor open. It’s not advanced math: if the politicians fail, and they probably will, Fitzpatrick will close.

You might think that closing Pilgrim would enable Entergy to devote more resources to Fitzpatrick and keep it open. But, as former nuclear executive Arnie Gundersen explains, Entergy’s support personnel, based in Mississippi, were spread over seven nuclear sites, three with Pressurized Water Reactors (PWRs) and four with Boiling Water Reactors (BWRs). That changed with the shutdown of Vermont Yankee, a BWR. And now with the impending shutdown of Pilgrim, also a BWR, that leaves two of them: Grand Gulf and Fitzpatrick. Said Gundersen in an e-mail today, “Every nuke they shutdown increases the overhead costs on the remaining ones. It’s a death spiral.”

So, by the turn of the decade, fewer than half of those 15 reactors that once populated New England, will be operating. And while, in that region–unlike the Midwest where wind power has become perhaps the major competitor to existing reactors–low natural gas prices are a prime reason for the rash of reactor shutdowns, in the long run the beneficiary is clean energy. With the capacity of Pilgrim, and soon Fitzpatrick, removed from the region, there is suddenly a wide opening for more renewables deployment. And, as regular readers of GreenWorld know, nuclear power and renewables don’t play well together. Moreover, renewables are now cheaper than nuclear power–even than existing reactors. The inevitable result is what we’re already seeing in Vermont: a renewed commitment from the state to a 90% renewable power system by mid-century, if not sooner. That obviously cannot occur when large nuclear reactors are operating; their shutdown is a necessity to be able to attain a clean, safe, and affordable nuclear-free, carbon-free energy future.

New England is now leading the way in building that system. But it didn’t happen by itself. It took dedicated groups of activists, too many to list here, committed to the long-term, committed to educating (first themselves, then the public), organizing and mobilizing, and never giving up. Let’s do that everywhere.

By the way, if you’re in New York, you can take one easy step by signing a petition sponsored by our friends at the Alliance for a Green Economy in support of Fitzpatrick’s speedy shutdown. Just click here.

Michael Mariotte

October 13, 2015

Permalink: https://www.nirs.org/pilgrims-closure-and-whats-next-for-new-england/

Your contributions make publication of GreenWorld possible. If you value GreenWorld, please make a tax-deductible donation here and ensure our continued publication. We gratefully appreciate every donation of any size.

Comments are welcome on all GreenWorld posts! Say your piece. Start a discussion. Don’t be shy; this blog is for you.

If you’d like to receive GreenWorld via e-mail, send your name and e-mail address to nirs@nirs.org and we’ll send you an invitation. Note that the invitation will come from a GreenWorld@wordpress.com address and not a nirs.org address, so watch for it. Or just put your e-mail address into the box in the right-hand column.

If you like GreenWorld, help us reach more people. Just use the icons below to “like” our posts and to share them on the various social networking sites you use. And if you don’t like GreenWorld, please let us know that too. Send an e-mail with your comments/complaints/compliments to nirs@nirs.org. Thank you!

GreenWorld is crossposted on tumblr at https://www.tumblr.com/blog/nirsnet

Thank you!!! to everyone in New England for helping close the Pilgrim reactor. Renewable energy can now power New England again. When the Pilgrims first came here, renewable energy was their power source. Not too long after arriving here, the colonists used the skills they acquired in their old countries to put up water-powered saw mills in their new country. Then came all the foundries, machine shops and textile factories, along with many new tools and machines. The axe is just one example of many. The Collinsville Axe Company (in Collinsville Conn.) made an axe-head using water that came from 25 miles upstream before it turned the belts, pulleys, and shafts that powered their machinery. Then there was James B. Francis, a 22-year-old from England who invented the Francis Turbine. Dams world-wide still use this style of water turbine 150 years later. One great part of renewable energy is–nothing is left over that cannot be used again. The same cannot be said of all the irradiated metals produced by atomic energy, one of two “products” made by that industry. The other “product” is nuclear waste. Some believe that nuclear waste is still a viable energy source. Hmm… making that work is about as likely as the Sun will start rising in the West.