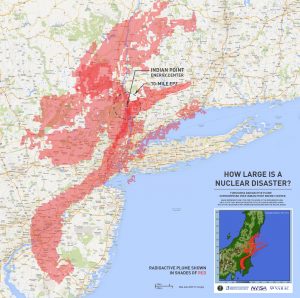

Emergency response plans only work as well as they are designed, and only if they are followed, and only if decision-makers have timely, accurate information. The track record of nuclear accidents follows a similar pattern, from Three Mile Island in 1979, through Chernobyl in 1986, to Fukushima in 2011. In each case, the operators of the reactor failed to give accurate, timely information to government officials, delaying actions that could and should have been taken to protect the public. In every corporate, government, and political organization, there is a tendency to hide and downplay negative information from the public, superiors, and competitors, and the monumental scale of a nuclear disaster only amplifies the pressure on people to hide their failures from scrutiny. In addition, there has long been a lack of confidence in how realistic and effective nuclear emergency response plans in the US are, based in part on inadequate regulatory requirements, but also the practical realities of nuclear disaster scenarios: fast-breaking, unanticipated events, relying on people to behave rationally and follow all instructions, with contamination dispersal heavily affected by changing wind and weather conditions, etc. NIRS documented the common failures in emergency response planning and proposed new regulations to the Nuclear Regulatory Commission. Unfortunately, NRC refused to act.