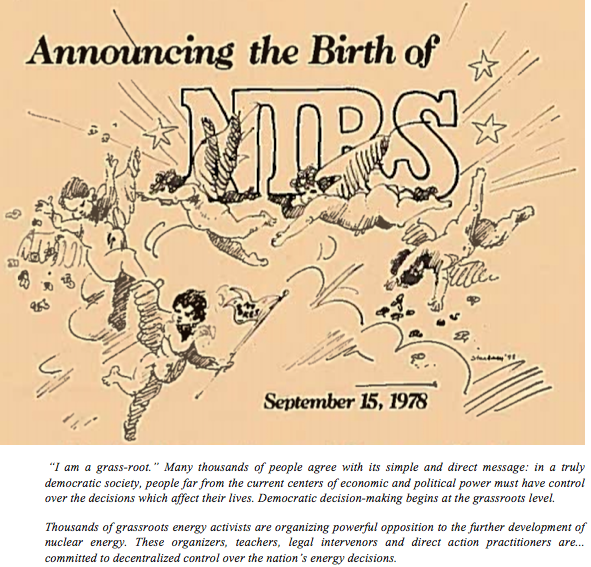

This year, the Nuclear Information and Resource Service (NIRS) will celebrate 40 years of tireless nuclear-free, carbon-free advocacy. When I joined NIRS in 2016, my staff position as Energy Democracy Specialist was a new venture for the organization. Yet the commitment to democratic decision-making, ownership and control of decentralized energy resources has been at the heart of NIRS’ advocacy from the very beginning. Opposition to nuclear energy is not just about protecting the environment or current and future populations from the harmful extractive processes, dangerous radioactivity, or disastrous and multi-generational effects of toxic exposure to nuclear waste. It is also about expressing and protecting the democratic principles at the heart of our political system.

This year, the Nuclear Information and Resource Service (NIRS) will celebrate 40 years of tireless nuclear-free, carbon-free advocacy. When I joined NIRS in 2016, my staff position as Energy Democracy Specialist was a new venture for the organization. Yet the commitment to democratic decision-making, ownership and control of decentralized energy resources has been at the heart of NIRS’ advocacy from the very beginning. Opposition to nuclear energy is not just about protecting the environment or current and future populations from the harmful extractive processes, dangerous radioactivity, or disastrous and multi-generational effects of toxic exposure to nuclear waste. It is also about expressing and protecting the democratic principles at the heart of our political system.

Hazel Henderson, a prominent ‘futurist’ and ‘economic iconoclast’ of her time, described nuclear energy as “inherently totalitarian” and “incompatible with democratic forms of government.” Her reasoning cites nuclear plants’ tendency for centralized authority, the necessity of high levels of social and capital investment, the risks and vulnerabilities they possess, and the way nuclear power “systematically disenfranchise[s] the public from decisions,” as evidenced by the widespread grassroots anti-nuclear mobilizations of 1970s and 80s – of which NIRS was a part. Matthew J. Burke concurs that “grassroots, democratic resistance” to nuclear power, combined with the technology’s failure to remain financially solvent despite years of “tremendous, deliberate political and economic backing” suggests real tensions between nuclear energy and democratic politics.

Nuclear power starts with uranium mining, an extractive process that has historically relied on an exploitative industry. The World Nuclear Association admitted that in ‘emerging uranium producing countries’ — which are frequently countries of the ‘global south’ — there exist no adequate environmental health or safety legislations to protect communities or the environment from the effects of the process, or to otherwise deal with the radioactive byproducts it produces. This demonstrates that nuclear energy perpetuates an industry founded upon international exploitation and a long-established wealth and resources transfer from less-developed to industrialized nations. The Natural Resources Defense Council’s 2012 report on uranium mining in the American West supported this conclusion, finding that the disproportionate effects on low-income or minority populations “represent[ed] an all too common pattern of environmental and economic injustice with respect to resource extraction.”

As complex as the technologies behind nuclear fission are, nuclear energy itself is a 1970’s solution that hasn’t aged well. As nuclear plants struggle to remain competitive in today’s energy markets, the industry’s pronouncements about the benefits of the technology have been revealed as overly optimistic. The extraordinary capital commitments that nuclear power demanded were justified by ‘economies of scale,’ which relied on expanding demand for constant output to keep costs down. Since then, advances in efficiency have led to stagnation in the growth of demand for energy — with no effect on productivity. Nuclear’s large and relatively steady generation, once praised, now makes these plants incompatible with a modern electric grid. Nuclear’s inflexibility inhibits the incorporation of renewables, and by so doing, undermines the ability for distributed, customer-centric energy.

Despite declining profitability compared to renewable energy, the potential for catastrophic radioactive disaster, and the inter-generational and therefore inherently unsafe consequences of nuclear waste, the nuclear industry has achieved special compensation for certain of its plants in some states. This has to do with their designation as ‘zero-emissions’ energy sources, demonstrated by the fact that nuclear produces no greenhouse-gas emissions during energy production, unlike traditional fossil-fuel power plants. Yet nuclear energy is a false solution to climate change, as NIRS and our international coalition of advocates under the Don’t Nuke The Climate campaign will tell you. Continued investments in nuclear power will be at the expense of renewable generation, which is urgently needed to be brought online to address climate change.

Distributed ownership of renewable energy resources is the holy grail of energy democracy. When done correctly, there’s minimal environmental impact and the infrastructure is harmless. It would emit no greenhouse-gases or other pollution, and in fact could be a boon to local economies, by creating the need for various installation, maintenance, and monitoring services. And widely distributed ownership would mean more widely distributed benefits. Achieving energy democracy means transitioning from the centralized, secretive nature of the nuclear industrial complex, and instead advancing opportunities for “people far from the current centers of economic and political power to have control over the decisions which affect their lives.”

As NIRS turns 40, we look forward to reviewing our past work that has amplified the voices of communities across the nation — and populations across the globe – that demand recognition of the effects that nuclear energy and waste has had on their environment and physical well-being. Transparency, accountability, and the ability of the public to meaningfully participate in decision-making on energy policy are the foundational principles of energy democracy. My work advancing clean renewables is a fitting complement to NIRS’ anti-nuclear advocacy, since the nuclear industrial complex is diametrically opposed to a clean, modern, democratic energy system.