It is increasingly urgent to do all we can to end Russia’s war on Ukraine and achieve a peaceful withdrawal of Russian forces from the country. Untold thousands of civilians have now been killed. Over one-fourth of Ukraine’s population–more than 10 million people–have been displaced from their homes and cities, many of which have been completely devastated by deliberate targeting of residential areas, schools, hospitals, shopping malls, and government buildings where people have sought shelter. The suffering and destruction being wrought by Russia is as awful as anything we have seen in recent history: the US war on and occupation of Iraq, the proxy civil war in Yemen, the Syrian civil war and Russia-led devastation of Aleppo, and others.

But there is a glaring complication in this war: the very real and immediate risk of its escalating to nuclear devastation. Russia possesses the world’s largest arsenal of nuclear weapons, and has had them on high alert since February 28. Yesterday, government spokesperson Dmitry Peskov stated that Russia would only use them if there is “an existential threat” to the country. The tensions between Russia and the NATO alliance, which centrally includes the US and other nuclear weapons states, make it essential to avoid a broader regional or global war.

An even more immediate danger has been explicit from the very first day. The presence of civilian nuclear power plants and Russia’s decisions to attack and occupy those sites with its military. Russia’s direct attacks on and occupation of the Chornobyl and Zaporizhzhia sites are among the most reckless acts of the war. They threaten to unloose disasters which Russia has literally no means of controlling, with effects that would not only encompass the whole of Ukraine but much of Europe and Asia. There has been some media coverage of these dangers, but most has been poorly informed by proponents of nuclear energy who either downplay the actual risks or seem unfamiliar with them.

Here is what we know so far:

- Russia assaulted and took control of the Chornobyl nuclear disaster site on February 24. Military convoys have dispersed radioactive contamination from the 1986 fallout in the uninhabitable exclusion zone, and military forces have set fires in contaminated areas. Russia cut off power to the site for several days, preventing proper cooling and ventilation in the enclosure facility protecting the melted core of the destroyed reactor #4. The power outage also stopped cooling of the pools with 20,000 irradiated fuel assemblies from reactors 1, 2, and 3. Chornobyl staff who were working when Russia invaded were forced to work and live on-site for three weeks, suffering from fatigue, lack of sleep, psychological distress, and inadequate food.

- On March 4, Russia attacked and occupied the Zaporizhzhia Nuclear Power Plant, the largest reactor site in Europe. Russian forces attacked not only an administrative building and prevented fire fighters from putting it out for hours; they also shelled one of the reactor buildings and damaged one of the transformer yards, cutting off some of the electrical supply to the site. Two of six reactors continue generating electricity. The Russian military is using the site as a staging area, with weapons, ordinance, and explosives on-site.

- On March 26, as well as on March 6 and March 10, Russia attacked a research reactor at the Kharkiv Institute, damaging the reactor building and some of its electrical cables and infrastructure. The reactor has been put into cold shutdown, but remains vulnerable to a direct military strike.

- The Ukrainian nuclear safety agency, SNRIU, has not had access to Chornobyl, Zaporizhzhia, the workers, or radiation monitoring networks at those sites for weeks now. Staff at the plants have been working under Russian military occupation. And Russia’s nuclear power company, Rosatom, has staff at Zaporizhzhia, doing what it is not clear. IAEA has no access to monitoring information from Chornobyl facilities.

Russia’s occupation of the nuclear sites–and the likelihood that it would do the same at Ukraine’s three other nuclear power plants if its forces advance–serves several purposes. It enables Russia to hold Ukraine hostage to power outages, especially because 50% of the country’s electricity supply is generated by the nuclear plants. It enables Russia to stage its military operations from locations it knows Ukraine will not attack. And occupying the nuclear sites enables Russia to hold a sword of Damocles over not just Ukraine, but the whole of Europe–where people are still living with contamination from the Chornobyl disaster since 1986.

All of these purposes are unacceptable and risk nuclear disaster. For instance, even if Ukraine does not attack Russian military forces at Zaporizhzhia or Chornobyl, the munitions now stored there could accidentally catch fire and detonate. Nuclear safety regulations place strict controls on flammable and explosive materials being located and stored on commercial reactor sites for just that reason.

Certain extreme events, like aerial bombing or missile strikes, could break the containment building and destroy the reactor, but that is far from the only way for a nuclear disaster to occur. Three Mile Island, Chornobyl, and Fukushima proved that reactor meltdowns can be caused by a wide variety of problems. The forces released by a meltdown can burst the containment structure from the inside, causing radioactive contamination to escape. There are several concrete dangers, any of which could lead to widespread contamination:

- Nuclear reactor meltdowns: As the Fukushima disaster demonstrated, meltdowns of nuclear reactors can be caused by damage to power supplies, cooling systems, and other essential equipment that is located outside of the thick concrete-and-steel containment structures that typically enclose the reactor itself. The same is true of the VVER model reactors at Zaporizhzhia and Ukraine’s three other operational nuclear power plants. For operating reactors and those that have recently shut down, the massive amount of heat generated by the irradiated fuel in the reactor cores can quickly boil off the remaining water in the reactor vessel, and over-pressurize the reactor vessel and primary coolant system. The zirconium cladding on the fuel rods also causes steam to separate into hydrogen and oxygen, creating the risk of a large detonation, as happened at three of the Fukushima reactors. When fuel rods catch fire and melt, the molten mass can burn through the reactor vessel, and potentially cause water accumulating on the floor to flash into a steam explosion. The force of such detonations may be large enough to burst the containment structure, allowing large amounts of radiation to escape, uncontrolled and unfiltered. Even if the containment building does not crack, valves and seals on ventilation ducts, pipes, and entryways could break, allowing contamination to escape.

- Irradiated fuel: The operating reactor sites and spent fuel storage of Chornobyl Nuclear Power Plant contain thousands of tons of irradiated nuclear fuel. Most is stored in cooling pools, which depend on constant recirculation of water. If cooling is lost to a fuel pool, or water is drained out of it, the fuel can generate hydrogen, catch fire, and melt down. Once the water is drained and the fuel is uncovered, the radiation fields in the surrounding area are far too high for workers to enter the area and add water to the pools. Unlike at Chornobyl and at reactors in the US, fuel pools at most of Ukraine’s VVER reactors (those of the VVER-1000 design) are located inside the containment structure. While this could limit the amount of radiation released to the outside environment in a fuel fire, it creates what is referred to as a “common cause failure” scenario. If the reactor melts down, then the pool is likely to lose cooling, as well, virtually guaranteeing that a fuel pool fire will occur. The magnitude of radiation releases inside the containment would be far larger, thereby increasing the amount of radiation released to the outside environment. Subsequent hydrogen explosions from the fuel pool would increase the chance that containment would fail.

- Chornobyl fuel pool: Over 20,000 fuel assemblies from all four reactors that operated at Chornobyl are stored in a large fuel pool. As at US reactors, it is housed in a standard commercial-grade building. The fuel at Chornobyl has been cooling for over twenty years and has a much lower level of residual heat than the fuel in the pools at the operating reactor sites, meaning it would take much longer for the water to boil off when cooling is lost. However, the water could eventually boil or evaporate off, making the building inaccessible to workers and creating the potential for hydrogen explosions. As explained below, the Russian military’s occupation of the site means the potential for explosives to damage the fuel pool building, the cooling systems, and the irradiated fuel itself is quite real. A fuel pool fire at Chornobyl could release even more long-lived radioactive contamination than the 1986 disaster.

- Chornobyl site enclosure: After the explosion and meltdown, the destroyed reactor building was quickly enclosed in a concrete structure, in order to contain the radioactive material. But because it was so quickly built, it started to degrade very quickly. A new $2 billion confinement structure had to be built, and was finally put in place in 2016. The new confinement structure is designed to last 100 years, and includes ventilation, air filtration, radiation monitoring, and other systems to prevent the molten core material from overheating and to prevent further releases of contamination. The structure is not built to withstand military attack. If it is hit directly or accidentally, radiation could be released and ventilation and filtration systems rendered useless. Also, when power is lost to the site, the ventilation and filtration systems stop working. Moisture and heat then build up in the confinement, potentially damaging equipment and causing the structure to corrode.

- Chornobyl exclusion zone fires: The land surrounding the Chornobyl site is still highly contaminated. Due to the buildup of dead trees and vegetation, wildfires have occurred repeatedly in the summer months, which releases radiation into the air and spreads further downwind. The presence of the Russian military and its use of Chornobyl as a staging area increases the risk of more and greater fires, and is likely to interfere with firefighting efforts. Several wildfires in the exclusion zone were reported last week, based on satellite imagery.

The war entails new and greatly increased risks that these scenarios could occur:

- Loss of offsite power: The nuclear power plants and the Chornobyl site require a constant supply of electricity to operate cooling, ventilation, and other safety systems. If transmission lines are damaged or power supply is lost for any reason, the sites must rely on backup diesel generators to provide power. Zaporizhzhia’s backup generators have a bad reliability record, and spare parts are not readily available because of the war. The supply of diesel fuel is limited: only about one-week’s worth was stockpiled on-site when Russia attacked. It has been nearly three weeks, and the transformers damaged in the initial assault have still not been repaired.

- Flooding or cooling water loss: Zaporizhzhia is downstream of a dam. If breached, a wall of water could flood the site, potentially knocking out power and other infrastructure. Similarly, the primary cooling water source for the Zaporizhzhia reactors is a water impoundment on-site. If that reservoir were breached, it could drain the cooling water supply for the reactors. In either scenario, it could create an unstoppable meltdown scenario similar to what occurred at Fukushima in 2011.

- Human error: Workers at Chornobyl and Zaporizhzhia are living and carrying out their duties under physically terrible and psychologically strenuous conditions. They must continue working under military occupation, while their homes and families are under assault. They are facing shortages of food and medicine, just like the rest of the population. The trauma and stress of the experience is likely causing many to lose sleep and suffer fatigue. Workers at Chornobyl were confined to the site for the first three weeks, unable to get any rest or decent food, making most of them unable to work after several days. They may lack access to clean uniforms and protective gear, as was reported of the Chornobyl workers. This can increase stress and worry for their health. Workers likely see themselves as sacrificing their safety and well-being to protect their country from a nuclear disaster. It is hard for anyone to perform their jobs at a high level under these conditions, never mind extremely stressful jobs requiring a high level of technical knowledge and expertise. Under these conditions, the chances that mistakes could lead to a nuclear accident are far greater than normal.

- On-site conflict: Conflict and mistrust among the Ukrainian workforce and the Russian occupiers could result in violence. Vital workers could be wounded or killed, safety equipment could be damaged, and other unpredictable events could lead to a nuclear accident. Importation of other Rosatom employees to take over the site could not only exacerbate that danger, but also increase risks of human error by introducing staff who do not know the plant or how it has been maintained and operated under Ukrainian safety regulations.

- Military attacks: The military conflict could result in either intentional or accidental strikes on the nuclear plant. While the reactors themselves are somewhat protected by the thick concrete and steel containment structures, many of the essential safety components are not: cooling and fire suppression pumps, electrical supplies, diesel generators, etc.

- Sabotage: Nuclear safety regulations include tight security protocols for everyone who has access to reactor sites: nuclear workers, contractors, inspectors, visitors. That includes background checks, licensing and badging systems, security checkpoints, metal detectors, etc. These norms and regulations have already been fundamentally undermined by the presence of the Russian military, the involvement of Rosatom employees, removal of Energoatom’s and SNRIU’s access and authority, and disruption of the nuclear workforce. It is not clear how access from saboteurs is to be prevented under these conditions.

- Doomsday scenario: As the war progresses, one or both sides may become more desperate. For instance, if the invasion fails and Russia is forced to retreat, would Putin order an attack on, or sabotage of, Ukrainian nuclear sites in order to punish and disable Ukraine by unleashing nationwide, intergenerational devastation?

If a disaster were to happen, there is no possibility of effective emergency response under the conditions Russia has created. Access to accurate, real-time information has been bad enough in “peace-time” nuclear disasters like Three Mile Island, Chornobyl, and Fukushima. The war and occupation of the nuclear sites has made that impossible in Ukraine. Local and national governments cannot stage emergency response activities, or even communicate reliably. The Russian military targets civilian vehicles, making it impossible to evacuate people quickly, if at all. There is no way for many people even to “shelter in place” in much of Ukraine because buildings and homes have been destroyed. Setting up evacuation shelters, decontamination equipment, and medical treatment is out of the question. The whole of occupied Ukraine is consumed by the war, and is in no position to respond to a potential nuclear disaster.

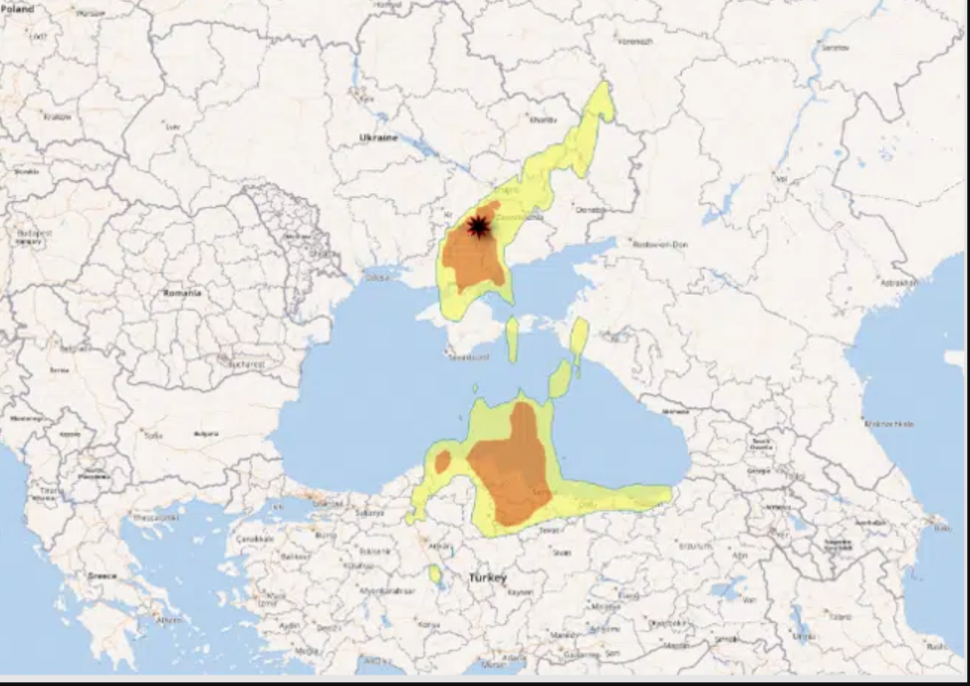

Depending on the scale of the disaster, other countries in the region could be severely affected. Contamination from the Chornobyl disaster had severe impacts on Belarus and Russia, as well as most of Europe. An analysis published in the Bulletin of Atomic Scientists confirms that a single reactor meltdown and/or fuel pool fire at Zaporizhzhia could force millions to evacuate in five countries. In addition, both Zaporizhzhia and Chornobyl are located on the Dnieper River, which provides drinking water to millions of people and feeds into the Black Sea. If contamination leaks to groundwater, as at Fukushima, there could be severe consequences to human health and the environment for the Black Sea region, and potentially downstream to the Aegean and Mediterranean seas.

Russia’s attack on Ukraine poses an existential threat to Europe and Asia – and the world – due to the nuclear dimensions of the conflict. The nuclear dangers of this war cannot and should not be underestimated. In supporting Ukraine, we must condemn the violence and warn US leaders about the nuclear complications of this war. There is a concrete action that the US can take to deter and condemn Russia’s nuclear violence on Ukraine: Sanction the Russian nuclear industry. If the US does not directly and forcefully sanction Russia for these acts, we risk allowing this war to establish a new international norm, making nuclear power plants legitimate military targets.