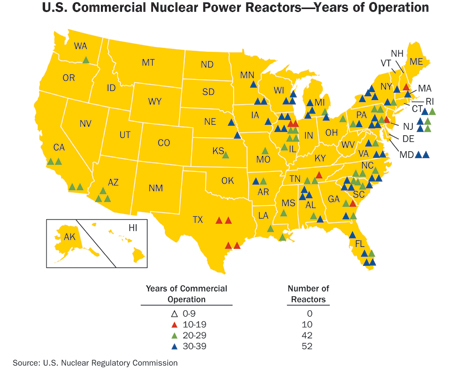

Last week, CNBC ran a story sure to elevate the blood pressure of clean energy activists everywhere: No more nukes? How about another 80 years of them. The article discussed the hopes of some in the nuclear industry that reactors will be able to be re- re-licensed and operate for 80 years instead of the original 40-year license period as well as beyond the 60 year license most U.S. reactors (75 of the 99 operating) already have received.

CNBC named names too: it said that Exelon, Duke Power and Dominion Resources are all considering applying for an additional 20-year extension to be able to operate for 80 years. Exelon is thinking about it for its Fukushima-clone Peach Bottom reactors in Pennsylvania, Dominion for its Surry reactors in Virginia and Duke Power for its Three Mile Island-clone three-unit Oconee plant in South Carolina.

The Nuclear Energy Institute quickly jumped on the bandwagon, posting on its website yesterday a piece titled Research Finds Few Obstacles to Long-Term Operations for Nuclear Plants. In NEI’s worldview, dedicated researchers from the Department of Energy and the nuclear industry are working hard to identify any obstacles to running reactors as long and hard as possible. Their conclusion isn’t surprising: “Much work remains to be done, but early results indicate that there are no generic technical reasons to prevent well-maintained nuclear power plants from operating beyond 60 years…”

Before anyone gets too excited however, it should be noted that the NRC does not–at least not yet–even offer license extensions beyond 60 years. Last year, as CNBC points out, the NRC staff recommended issuing a new proposed rule that would set up a pathway for allowing for such extensions, but the Commissioners nixed the idea. That doesn’t mean the Commissioners will always veto the concept, but does indicate that they don’t think either the industry or the agency is ready to move down that road.

So don’t expect any 80-year licenses soon. The lead time for issuing a final rule, especially one guaranteed to be controversial, is long. First a proposed rule has to be developed, defended and published for public comment–and there will be a lot of public comment. Then the staff has to answer the comments, formulate the final rule and present it to the Commissioners, who can either accept it as is or send it back for more work. In either case, the process can take anywhere from a year–if everyone works really fast and there is little controversy–to two years or more, and that’s all before a single application can be submitted, much less considered and accepted.

So what is really going on here? Why is the concept suddenly making news now?

It all goes back to what we’ve been emphasizing since GreenWorld began publication, and even before: to 2013 when the nuclear power industry suddenly recognized that the costs of merely operating many of its aging nuclear reactors were escalating rapidly at the exact time costs of competing electricity generation sources, especially solar and wind, were falling drastically.

Old reactors with large repair costs closed: San Onofre and Crystal River. But so did two old reactors with relatively low operating costs, one of which even had little citizen opposition: Kewaunee and Vermont Yankee. It was the shutdown of Kewaunee in particular, a low-profile, seemingly low-cost reactor, that shook the industry to its core. If Kewaunee couldn’t compete in the new world of low-cost electricity generation, then a lot of reactors wouldn’t be able to compete.

And so began the ongoing plea for ratepayer bailouts and regulatory and legislative relief from Exelon, Entergy, FirstEnergy and the rest.

Then came what the industry saw as a potential life-saver for its aging, uneconomic reactors: the EPA’s Clean Power Plan (CPP). But the proposed CPP didn’t offer the kind of direct bailout the industry had been hoping for and, as we reported two weeks ago, the industry is increasingly dubious it will get that kind of bailout from the EPA in the final version, which is expected to be released in early August.

So now the nuclear utilities are hoping that the states will bail them out in the implementation of the Clean Power Plan. The industry’s basic argument is that reactors are providing low-carbon power and that it would be more expensive to replace them with renewables than to keep them operating.

Here, for example, is former Exelon CEO John Rowe making that case: “Even if we could pair renewables with massive storage, the cost [of generating low carbon electricity] will be multiples of the cost of electricity from nuclear energy.” Even as he says that though, Rowe admits that he “might have been quicker” than Exelon’s current management to close the utility’s uneconomic reactors. Given that some of Exelon’s reactors cannot sell power at a rate high enough to cover their operating costs, the idea that their renewable competition–which can and do sell power lower than Exelon’s nukes–would somehow be even more expensive doesn’t hold up.

The industry’s other approach is to put up roadblocks for deployment of renewables, for example by, as Exelon is attempting to do in Illinois, replacing Renewable Energy Standards with “Clean Energy Standards” (CES) that include existing nuclear, which would then crowd out renewables (e.g. if a CES calls for 25% clean energy and nuclear is already providing 25% of that state’s energy, new renewables would be blocked, not encouraged). Another approach is trying to stop the growth of renewables by arguing against their tax credits (although new nuclear receives similar tax credits) and challenging renewables’ “reliability” before bodies like the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC) and grid operators like PJM.

Occasionally you hear the argument that renewables should replace fossil fuel plants first and then nuclear, but that comes almost entirely from academics and outside nuclear boosters. The reality is that nearly all nuclear utilities also operate a large amount of coal and/or gas plants and don’t want to see those shut down either.

Clearly the industry needs state intervention to prop up economically failing reactors. But these also tend to be among the industry’s older reactors. If they’re going to reach the end of their 60-year licenses during the initial CPP period (which runs through 2030) or not long afterwards, or if there is doubt that they can operate even 60 years (and assuredly, there is a lot of doubt about that–no commercial reactor has yet held a 60th birthday party), then the states have much less incentive to try to rescue them. Why give them special benefits if they’re not going to be able to operate anyway?

The NEI and utilities also warn (as they have falsely so often in the past) of looming power shortages if reactors are forced to close early. As the CNBC report said, “By 2040 half of the nation’s nuclear power plants will have been operating for 60 years, and by 2030 the United States could experience electricity shortages if a significant number of nuclear plants are retired in a short period, according to the industry’s trade group, the Nuclear Energy Institute.”

Of course, if those reactors are going to close anyway because they can’t operate longer–not because of license restrictions but because of deterioration–then taking such warnings seriously would surely cause states to encourage more, not less, renewable deployment. More natural gas is the only other viable alternative. After all, as John Rowe flatly states, “New coal is not economic, new nuclear is not economic.” But encouraging more renewable deployment now would help hasten the end of those aging reactors. And renewables can be deployed much faster than any other generation source as well–fast enough to avert any potential power shortage.

You see where we’re going with this, right?

Enter the 80-year nuclear reactor license.

The reality is that virtually any mechanical device can run forever if you keep replacing its fundamental pieces. Your desktop computer has a lifespan of about five years before it’s hopelessly obsolete. But you could replace everything in the box it’s in and it will be a new computer with a new five-year lifespan. Since it’s in the same box, you can call it the same computer if you want. We don’t do that because it makes no financial sense to do so. It’s much cheaper to just buy a new computer.

A ten-year old flip phone can still make phone calls; if it dies, theoretically you could replace its insides and make it last forever. And it will still make phone calls. That would be stupid, since it would be more expensive than a new phone and still wouldn’t have the advances smartphones have achieved in the past 10 years.

Extend that out to anything: you can replace the engine and transmission, several times if necessary, of your car and make it run virtually forever. The Ford Model T’s and other antiques out there on the road show that’s true. But they’re limited to collectors because for transportation purposes, they’re expensive, not very useful, and don’t meet today’s safety standards.

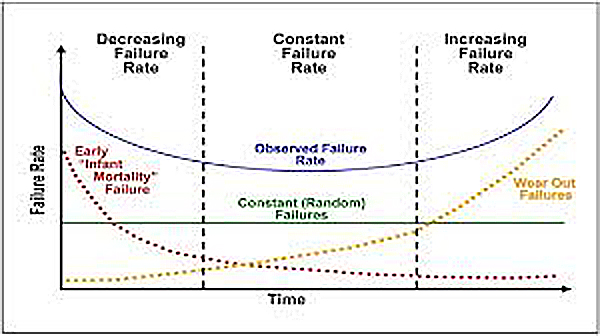

So yes, a nuclear reactor can operate for 80 years if you keep it in great shape and continually replace all of the old parts that need replacing. But at some point, the parts you’re keeping are obsolete. And the parts that need replacing–say, an embrittled pressure vessel–become too expensive (and in nuclear’s case, too dangerous to workers) to make any sense. And if you don’t replace a key old part in time, you might just cause the evacuation of a major city.

But from today’s current political perspective, with an industry increasingly desperate to save itself, it’s just the notion that reactors might be able to operate longer that is the selling point. Whether they actually can or not is almost irrelevant: the utilities aren’t worrying yet what happens with these reactors 20 or 30 years from now, they’re worried they’ll be forced to close them over the next couple of years.

From the perspective of the utilities with the endangered reactors–those that simply can’t compete economically anymore–the 80-year license concept is meant to reassure legislators, regulators, the public at large, that yes, these reactors will still be around, so there is good reason to support them now. It doesn’t matter to them that it’s not at all clear any reactor will make it to 60 years nor that most reactors haven’t yet even made it to 40 years, and far more have closed before reaching 40 than have made it to even that modest milestone.

While some of the research into aging reactors and the idea of extending their lives may be genuine and perhaps useful for specific components, the overall concept itself is not, and likely never will be, for cost reasons if not the increased risk to public safety already obsolete reactors present. It simply doesn’t make economic sense to try to bring old reactors up to even current safety standards, much less whatever standards will exist 20 years from now, most likely after the next Fukushima caused by yet unknowable factors leading to new safety regulations that can’t be met by old reactors.

In short, this is all just a PR game. And that’s why you’re seeing these kinds of stories now. Because the industry is trying to make sure you–and especially the policymakers–see them. They want to sell the idea that even their worst, failing reactors will still be around for decades. Otherwise, it wouldn’t make sense to give them any special treatment.

Of course, it doesn’t make sense, because most, probably all of these reactors, won’t be operating. And policymakers–at every level–need to understand that. What we should be preparing for, at the federal, state and grid levels, is precisely the shutdown of a significant and accelerating number of nuclear reactors over the next few years. Because that is by far the more likely outcome than their operation for decades longer.

Michael Mariotte

July 24, 2015

Permalink: https://www.nirs.org/80-years-not-very-likely/

Your contributions make publication of GreenWorld possible. If you value GreenWorld, please make a tax-deductible donation here and ensure our continued publication. We gratefully appreciate every donation of any size.

Comments are welcome on all GreenWorld posts! Say your piece. Start a discussion. Don’t be shy; this blog is for you.

If you’d like to receive GreenWorld via e-mail, send your name and e-mail address to nirs@nirs.org and we’ll send you an invitation. Note that the invitation will come from a GreenWorld@wordpress.com address and not a nirs.org address, so watch for it. Or just put your e-mail address into the box in the right-hand column.

If you like GreenWorld, help us reach more people. Just use the icons below to “like” our posts and to share them on the various social networking sites you use. And if you don’t like GreenWorld, please let us know that too. Send an e-mail with your comments/complaints/compliments to nirs@nirs.org. Thank you!

GreenWorld is crossposted on tumblr at https://www.tumblr.com/blog/nirsnet

80 years?

Our descendants will be lucky to have an energy system in 80 years, since the fossil fuels and minerals will be mostly gone before then.

Nuclear reactors take a lot of energy and resource inputs to manufacture. Steel. Concrete. Electronic controls. Wires. A money system based on endless growth through debt creation.

Whatever will (or will not) be done with the nuke waste will require concentrated energy to make casks, depositories, or any other scheme, plus moving heavy casks full of waste is unlikely to be done with solar and wind (and the roads and rails are not maintained and resurfaced with electricity). I don’t endorse ANY approach to the waste except ceasing its production.

(Even solar panels and wind farms take energy inputs and minerals to make.)

The oil wells are half empty, so business as usual is no longer physically possible.

The oil wells are half full, so we have some resources for the transition, if we all choose wisely.

You are so right here Mr Mariotte. I especially like your comparing replacing parts in a Model-T and a flip phone to replacing parts in a aged reactor. The “original” shell is just that. Of course the tons & tons of irradiated metals created are still with us.