By Mark Cooper

Within the past year, a bevy of independent, financial analysts (Lazard, Citi, Credit Suisse, McKinsey and Company, Sanford Bernstein, Morningstar) have heralded an economic revolution in the electricity sector. A quarter of a century of technological progress has led to the conclusion that over the course of the next decade a combination of efficiency, renewables and gas will meet the need for new resources and more importantly, render the antiquated baseload model largely obsolete.

The academic debate over whether we could get to an electricity system that relies entirely (99 percent) or mostly (80 percent) on renewables late in this century is largely irrelevant compared to the fact that over the next couple of decades we could see a rapid and substantial expansion of renewables (to say 30 percent of 40 percent), if the current economic forces are allowed to ply out and policies to advance the transformation of the electricity system are adopted.

Political revolutions tend to follow economic revolutions, which is where we stand in the electricity sector today. The dominant incumbents, particularly nuclear utilities, have recognized that they face an existential threat and they have launched a campaign to eliminate it. Utilities, which loudly announced the arrival of a “nuclear renaissance” less than a decade ago, are desperate to save their fleet of aging reactors from early retirement and “stay relevant to the game going forward” (as the CEO of Exelon, the nation’s largest nuclear utility put it) because they cannot compete at the margin with renewables or gas.

This nuclear v. renewables debate is not just “déjà vu all over again; a lot more than the fate of nuclear power is at stake. The fundamental approach to delivering electricity in the 21st century, while meeting the challenge of climate change, is on the table. Nuclear power and the alternatives are so fundamentally different that a strategy of “all of the above” is no longer feasible. Nuclear power withers in an electricity system that focuses on flexibility because it is totally inflexible, but renewables cannot live up to their full potential without opening up and transforming the physical and institutional infrastructure of the system.

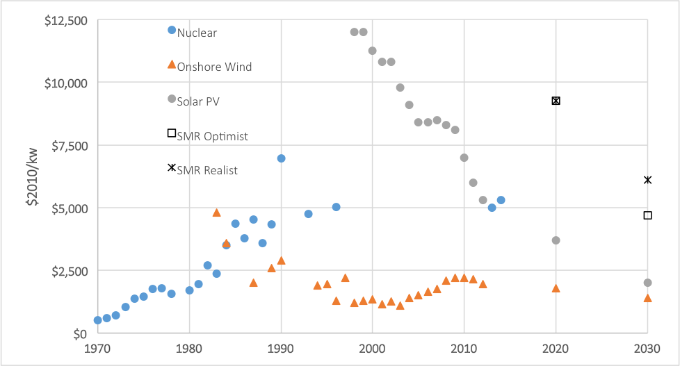

Nuclear power has failed because it has never been able to compete at the margin with other resources—coal in the 1980s, gas in the 1990s and renewables in the 2000s. Renewables have become competitive, not only because technological progress lowered the resource costs of supply dramatically, but also because the growth of information and control technologies have made it possible to integrate decentralized generation technologies into a dynamic two-way system that achieves reliability by actively managing supply and demand.

The ongoing efforts of Exelon and Entergy to change the rules in the regions of the U.S. that have relied most on market forces epitomizes the political conflict. Unfazed by the fact that the nuclear industry has been the recipient of ten times as much subsidy as renewables on a life cycle basis and continues to receive massive subsidies in the form of socialized cost of liability insurances and waste management, underfunded decommissioning, inadequately compensated water use, federal loan guarantee and production tax credits for new reactors, continuing R&D funding for small modular reactor technology, and advanced cost recovery for nuclear investment in a number of states, the nuclear industry launched its campaign for survival with an attack on the production tax credit for wind.

However, the campaign quickly moved beyond that small subsidy to demand much more pervasive changes in regulatory policy. Precisely because the economics of renewables have improved so dramatically, nuclear power needs to prevent the development of the physical and institutional infrastructure that will support the emerging electricity system.

Putting a price on carbon will not solve the fundamental problem because it picks losers (fossil fuels), not winners, and that is what nuclear needs because it is at such a huge economic disadvantage. It will give aging reactors a little breathing room, but it will not make them more competitive with renewables at the margin and it will certainly not address the need for institutional reform.

Economic dispatch, net metering, bidding efficiency as a resource, demand response, all of which are being fought by the utilities, are not about subsidies; they are about economic efficiency. The regulated physical and institutional infrastructure supported baseload power and retards the growth of the efficiencies of decentralized generation and system management. Nuclear power needs to jerry-rig the dispatch order so that they are guaranteed to run, create capacity markets that guarantee they win some auction, and redefine renewable portfolios to include nuclear.

Ironically the current terrain of resource choice and the attack on renewables reflect the fact that renewables have succeeded in exactly the way nuclear has failed. Relatively small subsidies unleashed powerful forces of innovation, learning and economies of scale that have caused dramatic reductions in costs, yielding a much higher return on social investment.

Renewable technologies are able to move rapidly along their learning curves because they possess the characteristics that allow for the capture of economies of mass production and stimulate innovation. They involve the production of large numbers of units under conditions of competition. They afford the opportunity for a great deal of real world development and demonstration work before they are deployed on a wide scale. These is the antithesis of how nuclear development has played out in the past, and the push for small modular reactors does not appear to solve the problem, as I showed SMR advocates have proposed.

The challenge now is to build new physical and institutional infrastructure. In fact, the growing literature on climate change makes it clear that the cost of the transition to a low carbon sector will be much lower if institutional change precedes, or at least goes hand in hand with pricing policy.

Mark Cooper

June 6, 2014

Mark Cooper is Senior Fellow for Economic Analysis, Institute for Energy and the Environment

Permalink: https://www.nirs.org/2014/06/06/1011-old-reactors-vs-new-renewables/

You can now support GreenWorld with your tax-deductible contribution on our new donation page here. PayPal now accepted. We gratefully appreciate every donation of any size–your support is what makes our work possible.

Comments are welcome on all GreenWorld posts! Say your piece above. Start a discussion. Don’t be shy; this blog is for you.

If you like GreenWorld, you can help us reach more people. Just use the icons below to “like” our posts and to share them on the various social networking sites you use. And if you don’t like GreenWorld, please let us know that too. Send an e-mail with your comments/complaints/compliments to nirs@nirs.org. Thank you!

Note: If you’d like to receive GreenWorld via e-mail daily, send your name and e-mail address to nirs@nirs.org and we’ll send you an invitation. Note that the invitation will come from a GreenWorld@wordpress.com address and not a nirs.org address, so watch for it.

on the graph, current costs for SolarPV seem way high.

Has been less than $1 per watt for quite a while.

We are interested in using the graph on trends in costs (nuclear, solar and wind) opeing this article. Could you send it as a PDF. Did the author Mark Cooper develop it, so we can credit properly.

No, we do not have a pdf version of this graph; you should be able to save it as a png file just by right-clicking it.